A Comprehensive Look

How Bedsores Form

So, what exactly is a bedsore? Also referred to as pressure ulcers, bedsores are injuries to the skin and underlying tissue that result from prolonged pressure on the skin. They commonly develop on areas of the body where bones are close to the skin, such as ankles, heels, hips, and tailbone. Patients confined to beds or wheelchairs for extended periods, especially without proper care, are at a heightened risk. These wounds can start as mild redness but, if left untreated, can progress to more severe stages, leading to deep wounds that expose muscle or bone.

At Bedsore.Law, we understand the gravity of this condition and recognize that its presence often signals neglect, particularly in healthcare facilities like nursing homes and hospitals. Our mission is to shed light on this issue, provide resources for affected families, and legally advocate for victims to ensure they receive the justice they deserve. Bedsore cases is what we specialize in.

We stand firmly against neglect and strive to ensure that everyone receives the proper care and dignity they deserve. Read more below to learn about bedsores.

Please click the links below to view the following sections:

- Decubitus Ulcer Development

- The Impact of External Factors

- The Influence of Internal Factors

- Role of Underlying Health Conditions

- Pressure Injury Classifications

- Prevention and Management

- Role of Health Care Providers

- Importance of Early Detection

- The Role of Family and Caregivers

- Challenges and Solutions

- A Patient-Centric Approach

- Role of Rehabilitation Professionals

- Involving the Patient

- Technological Advances

- Conclusion

Decubitus Ulcer Development

The development of decubitus ulcers, also known as pressure injuries, pressure ulcers or bedsores, is a complex process influenced by a combination of both internal and external factors. These ulcers represent a significant healthcare challenge, particularly in the realm of elder care and for those patients with prolonged periods of immobility due to illness, injury, or surgical recovery.

Decubitus ulcers result from continuous pressure exerted on a particular area of the body, most commonly those areas with bony prominences, such as the sacrum, heels, and elbows.

Several external factors amplify the risk of developing ulcers, including pressure, friction, shear force, and moisture. However, internal factors such as fever, malnutrition, anemia, and endothelial dysfunction can also speed up the process of lesion formation.

Remarkably, immobility for as little as two hours in a bedridden patient or a patient undergoing surgery can establish the foundation of a decubitus ulcer. This startling fact underscores the necessity of frequent position changes and vigilant monitoring for at-risk patients.

One significant mechanism in forming these ulcers involves the dysfunction of nervous regulatory mechanisms responsible for regulating local blood flow. Extended pressure on tissues can lead to occlusion of the capillary beds, thereby reducing oxygen levels in the area. Over time, ischemic (lacking sufficient blood flow) tissue accumulates toxic metabolites, ultimately leading to tissue ulceration and necrosis or tissue death.

Certain conditions predispose patients to decubitus ulcers, including neurological disease, cardiovascular disease, prolonged anesthesia, dehydration, malnutrition, and hypotension. Additionally, surgical patients represent a significant risk category due to the extended periods of immobility both during and after procedures.

Understanding the intricate factors that lead to decubitus ulcer development can guide preventive and therapeutic strategies. Comprehensive patient assessments, incorporating a broad view of the patient’s health and lifestyle, are vital in managing this prevalent healthcare issue.

The Impact of External Factors

External factors contribute significantly to the development of pressure injuries. Unrelieved pressure is the primary external cause. The pressure exerted on the skin and underlying tissues due to body weight, particularly over bony prominences, restricts the blood supply to these areas. If this pressure is not periodically relieved, the deprivation of oxygen and essential nutrients can eventually lead to cell death and tissue necrosis, resulting in an ulcer.

Moreover, other external factors, such as friction and shear force, contribute to ulcer development. Friction occurs when the skin rubs against a surface, causing damage to the superficial layers of the skin. This damage can make the skin more susceptible to pressure ulceration. On the other hand, shear force occurs when the skin and superficial tissues remain static, and the deep fascia and skeletal muscle slide down with gravity. This distortion can occlude the blood vessels, leading to ischemia and subsequent tissue damage.

Moisture is another crucial external factor, often overlooked. A damp environment, caused by factors like sweating or incontinence, can make the skin more prone to damage. Moist skin can increase friction and make the skin more susceptible to minor trauma, contributing to the likelihood of pressure ulcer development.

The Influence of Internal Factors

While external factors are crucial, internal conditions and comorbidities significantly contribute to the susceptibility of patients to decubitus ulcers. Fever, malnutrition, and anemia can impede the body’s repair of damaged tissue and maintain healthy skin integrity.

For instance, malnutrition is a well-recognized risk factor. Without proper nutrition, the body lacks the necessary proteins and nutrients to repair damaged tissue and maintain the strength and health of existing skin and muscle. Similarly, anemia deprives the tissues of the necessary oxygen, hindering tissue repair and exacerbating the effect of pressure-induced ischemia.

Endothelial dysfunction, characterized by the reduced availability of nitric oxide and an imbalance of vasodilatory and vasoconstrictive substances, also plays a role in pressure ulcer development. It can lead to microvascular dysfunction, an early occurrence in pressure ulcer formation.

Role of Underlying Health Conditions

Certain health conditions increase the risk of developing pressure injuries. Neurological conditions, particularly those that cause sensory deficits, can prevent patients from feeling the pain or discomfort usually associated with prolonged pressure. As a result, these patients might not make the movements or positional changes that typically help alleviate sustained pressure.

Patients with cardiovascular disease may also be at higher risk due to poor blood circulation, which can further exacerbate the ischemic conditions caused by prolonged pressure. Similarly, individuals under prolonged anesthesia, such as during and after surgery, are at an increased risk due to immobility and reduced sensory perception.

Furthermore, conditions that result in dehydration can make the skin more susceptible to breakdown, thus increasing the risk of pressure ulcer development. Hypotension, or low blood pressure, can also contribute to poor blood supply and the subsequent risk of tissue ischemia.

Pressure Injury Classifications

STAGE 1: The earliest stage of a bedsore, the skin is not broken but is red. The area may feel warm to the touch, be painful, and not turn white when pressed. In darker skin, the area may appear discolored but not red and may be harder to detect.

STAGE 2: The outer layer of skin (epidermis) and part of the underlying layer of skin (dermis) is damaged or lost. The wound may be shallow and pinkish or red, and it may look like a blister filled with clear fluid. Some skin may be damaged beyond repair or lost.

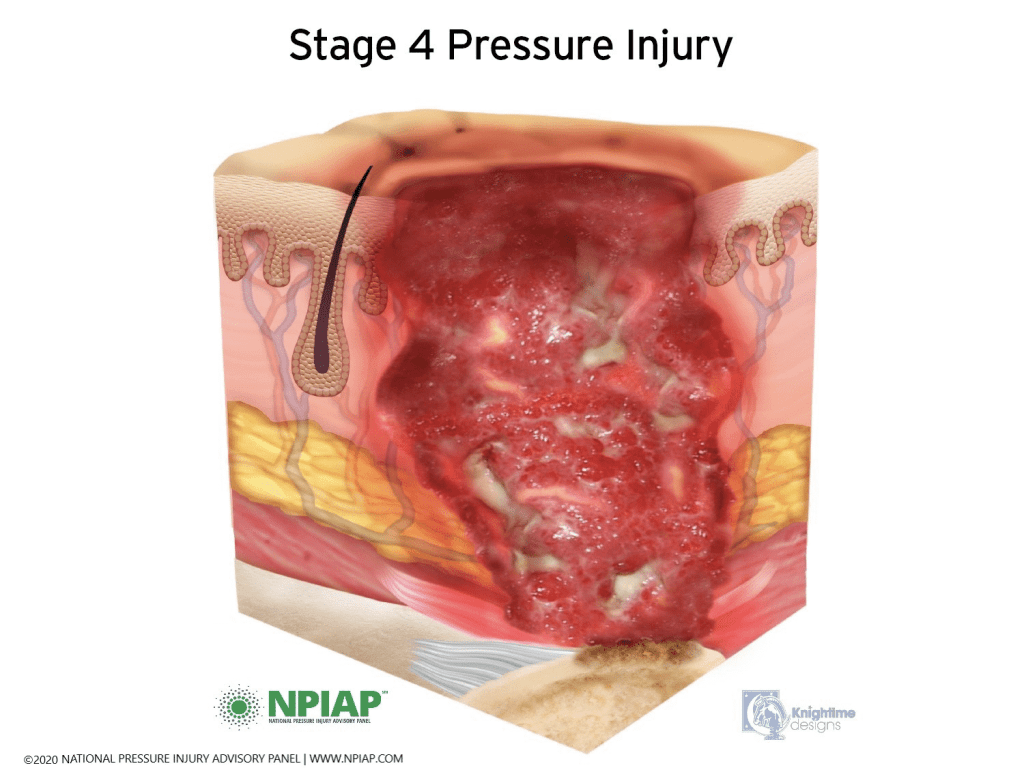

- STAGE 3: The ulcer is a deep wound: the loss of skin exposes some fat, and the ulcer can look like a crater. There may be some black tissue (called eschar) around the edges of the ulcer, which is damaged tissue that needs to be removed.

- STAGE 4: This is the most serious and advanced stage. Many layers are affected in this stage, including the muscle, bone, and supporting structures like tendons or joints. Extensive damage beneath the skin surface can create a large wound. Again, there may be some black tissue.

- UNSTAGEABLE (Stage 3 or 4): The National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) defines an unstageable pressure injury as “full-thickness skin and tissue loss in which the extent of tissue damage within the ulcer cannot be confirmed because it is obscured by slough or eschar.”

A DTPI is a pressure injury that presents as a localized area of discolored (purple or maroon) intact skin, or a blood-filled blister. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, firm, mushy, or warmer or cooler compared to adjacent tissue. Deep tissue injury may be difficult to detect in individuals with dark skin tones. Commonly referred to as a DTI.

Prevention and Management

Given the complexities associated with developing pressure injuries, a multifaceted approach is required for prevention and management. This approach includes regular patient repositioning, comprehensive skin care, adequate nutrition, and prompt management of incontinence.

Patient repositioning should be done at least every two hours for bedridden patients and every 15 minutes for patients sitting in chairs. The use of pressure-reducing devices like specialized mattresses or cushions is also recommended.

Skincare should focus on keeping the skin clean and dry. Frequent inspections are necessary, especially for vulnerable areas, to identify any signs of skin breakdown early. Moisturizers can help to maintain the elasticity and health of the skin, while barrier creams can protect the skin from the harmful effects of incontinence.

In terms of nutrition, a balanced diet rich in proteins, vitamins, and minerals is essential. Patients with poor nutritional status may require supplements or nutritional counseling to address deficiencies. Hydration is equally important; sufficient fluid intake maintains skin elasticity and helps the body’s overall functioning.

Effective management of incontinence can prevent skin maceration that comes with prolonged exposure to moisture. This management can include scheduled toileting, using absorbent products, and skin cleansing after each incontinence episode.

Role of Health Care Providers

Healthcare providers play a pivotal role in preventing and managing pressure injuries. Regular training and education are needed to ensure that all staff know the risk factors, prevention strategies, and early signs of pressure ulcers. It is important to note that prevention is always better – and less costly than treatment. Therefore, a proactive approach is highly beneficial.

Healthcare providers should collaborate to develop and implement individualized care plans for each patient, especially those at high risk. These care plans should include repositioning schedules, dietary plans, skin care regimens, and incontinence management strategies.

Importance of Early Detection

Early detection of pressure injuries can drastically improve the prognosis and reduce the severity of the condition. Healthcare providers should perform regular skin assessments, especially in high-risk patients, to identify early signs of pressure ulcers, such as persistent redness, warmth, swelling, or skin hardness. Any suspected skin changes should be reported and documented promptly.

A pressure injury’s location can give a hint about the contributing factors. For instance, ulcers on the back of the head might indicate an issue with the patient’s head positioning in bed, while ulcers on the heels might suggest a need for pressure-relieving footwear or devices.

The Role of Family and Caregivers

Family members and caregivers also play a crucial role in preventing and managing decubitus ulcers. They can assist in repositioning the patients, providing skin care, ensuring adequate nutrition, and reporting any early signs of skin breakdown. Their involvement is particularly significant in home care settings where professional healthcare providers are absent.

Family and caregivers should be educated about pressure ulcer risk factors and prevention strategies. They should be encouraged to actively participate in the patient’s care plan and voice any concerns or suggestions.

Challenges and Solutions

Despite our understanding of the causes and prevention strategies, pressure injuries remain a common problem in healthcare settings, indicating a gap between knowledge and practice. Some of the challenges include understaffing, inadequate training, and the lack of standardized prevention protocols.

Addressing these challenges requires a concerted effort from all stakeholders, including healthcare providers, administrators, policy-makers, and families. Investment in staff training, development and implementation of evidence-based protocols, and fostering a culture of quality improvement can significantly reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers.

Furthermore, research should continue to better understand the complexities of pressure injury development and develop more effective prevention and treatment strategies. Technological advancements, such as pressure mapping systems and advanced wound care products, offer promising avenues to help tackle this pervasive issue.

Pressure injuries are a significant healthcare issue that results from a complex interplay of various external and internal factors. A comprehensive and proactive approach is necessary for their prevention and management.

While we have made considerable strides in understanding and managing pressure ulcers, we still have a long way to go to completely eradicate this pervasive issue. With concerted efforts from healthcare professionals, patients, and caregivers, and the continual advancement of research and technology, we can hope to see a significant reduction in the occurrence of these distressing wounds.

A Patient-Centric Approach

A key element in preventing pressure injuries is adopting a patient-centric approach. Each patient’s needs, lifestyle, and overall health status should be considered when devising a prevention and care plan. The plan should be regularly updated as the patient’s condition changes.

For instance, if a patient has a neurologic condition affecting their sensory perception, they might not feel discomfort from prolonged pressure, which calls for regular, scheduled repositioning. Similarly, if a patient is prone to incontinence, their skin might be more susceptible to moisture-associated damage, and hence, a robust skincare routine and incontinence management plan are necessary.

Role of Rehabilitation Professionals

Rehabilitation professionals, such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists, can make valuable contributions to preventing and managing decubitus ulcers. They can help patients improve their mobility and perform regular movements, reducing the sustained pressure that contributes to ulcer formation.

Furthermore, they can help patients adapt to mobility aids and teach them exercises to improve blood circulation. In cases where patients have developed ulcers, rehabilitation professionals can suggest optimal positioning and movements to alleviate pressure on the affected areas, promoting healing and preventing the worsening of existing ulcers.

Involving the Patient

Patient involvement is equally important. Educating patients about the risk factors and signs of pressure injuries can help in early detection and prevention. Patients should be encouraged to report any discomfort, pain, or changes in their skin condition.

In cases where the patient’s mobility is not severely compromised, they can be taught to reposition themselves regularly or perform simple exercises to improve circulation.

Technological Advances

Technological innovations can potentially revolutionize the prevention and treatment of pressure injuries. Advanced wound dressings that maintain an optimal wound-healing environment, pressure-relieving mattresses and cushions, and smart devices that alert caregivers when it’s time for patient repositioning are just some of the innovations that can help in the fight against pressure ulcers.

In the future, we can expect further advancements in this field. For instance, machine learning algorithms could potentially be used to predict a patient’s risk of developing pressure ulcers based on their individual health data, enabling early preventive interventions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the battle against decubitus ulcers is multifaceted, requiring concerted efforts from various stakeholders. By enhancing our understanding of this complex condition, improving our prevention and treatment strategies, and leveraging technological advancements, we can hope to significantly reduce the burden of decubitus ulcers. The focus should always remain on providing patients the highest quality of life, ensuring their comfort, dignity, and well-being.